Not all those who wander are lost. – J.R.R. Tolkien

Choosing a mini-adventure over a late afternoon nap, I laced on the mocs and headed across Esplanade Riel to Le Musée de Saint-Boniface.

While the museum is filled with fascinating objects, including the half-burnt coffin of Louis Riel, the principal artifact is the building itself.

It was constructed as a convent for The Sisters of Charity of Montreal (“Grey Nuns”) who arrived in 1844 to provide social services/missionary work to the Red River Colony. It is of Red River Frame construction, the oldest building in the City of Winnipeg, and the largest oak log structure in North America.

Jill Wade, in her paper Red River Architecture 1812-1870, details this form of construction:

It is made of log construction common to Manitoba and given a variety of names: Manitoba frame, Red River frame, piece sur piece, poteaux sur sole, poteaux et piece coulissante, and the Hudson’s Bay style. As some of these names suggest, the building type grew from strong French influences, but actually originated in Denmark and Scandinavia…

The style was introduced to North America by the settlers of New France and brought west with the fur trade. Eventually, it was adopted by the employees of the HBC. It was used to build Fort Douglas, the Selkirk settlers’ first fort, and remained popular for homes, churches, stores and outbuildings throughout the area until the 1870s. An increased availability of manufactured materials late in the century made elaborate homes possible and common homes easier to build, log buildings lost their popularity.

The Red River frame building started with a frame of hand-squared logs, often oak, resting on the ground or a foundation. This foundation could be built of any readily available material, which on the prairies often meant a mixture of fieldstones and mortar. Sill logs were placed atop the foundation, then vertical members were tenoned at the corners and along the sill. These vertical logs were grooved in order to accept the tapered ends of horizontal logs placed between the uprights. Doors were often set between two minor uprights, windows similarly established or were simply cut out of the wall, with the rough hewn window frames nailed to the free ends of the logs.

It has, in turn, been a hospital, orphanage, senior citizen’s home, day school, boarding school, and a nursing college for students of St. Boniface General Hospital, which was operated by the Grey Nuns. In 1956 the Grey Nuns vacated the building and in 1958, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada designated the building as a historic site, recommending that it be preserved for possible use as a museum, as it soon became.

I met Museum Director Philippe Mailhot on the stoop. Although I am a management consultant, alas I wasn’t the consultant he was waiting for. I toured the two floors of the museum alone and then peppered the poor woman at reception with my construction-related questions. She kindly summoned Georges Lavergne, Maintenance Foreman and part-time builder, and we promptly descended to the basement, always the best place to begin an architectural exploration.

The building is intriguing both for its original construction style as well as for the thorough work undertaken between October 1993 and May of 1995 to restore the historic fabric of the building.* Seems the walls were pulling apart, as witnessed by the visible tenons on the second floor. Vertical steel posts have been sunk into the basement floor and run the full height of three floors. Glulam or steel I-beams have been added to each floor, and all the posts and glulam beams have been clad in spruce to blend with the original structure. Steel cables help to lock the walls in place. Maybe this work wouldn’t be remarkable on a contemporary structure. However it is a complex undertaking in a building where most of the wood members have deflected over time, some remarkably so. Little is plumb, square or level. It would have required extraordinary attention to detail and continuous problem-solving to complete this work on time, on budget and according to specs.

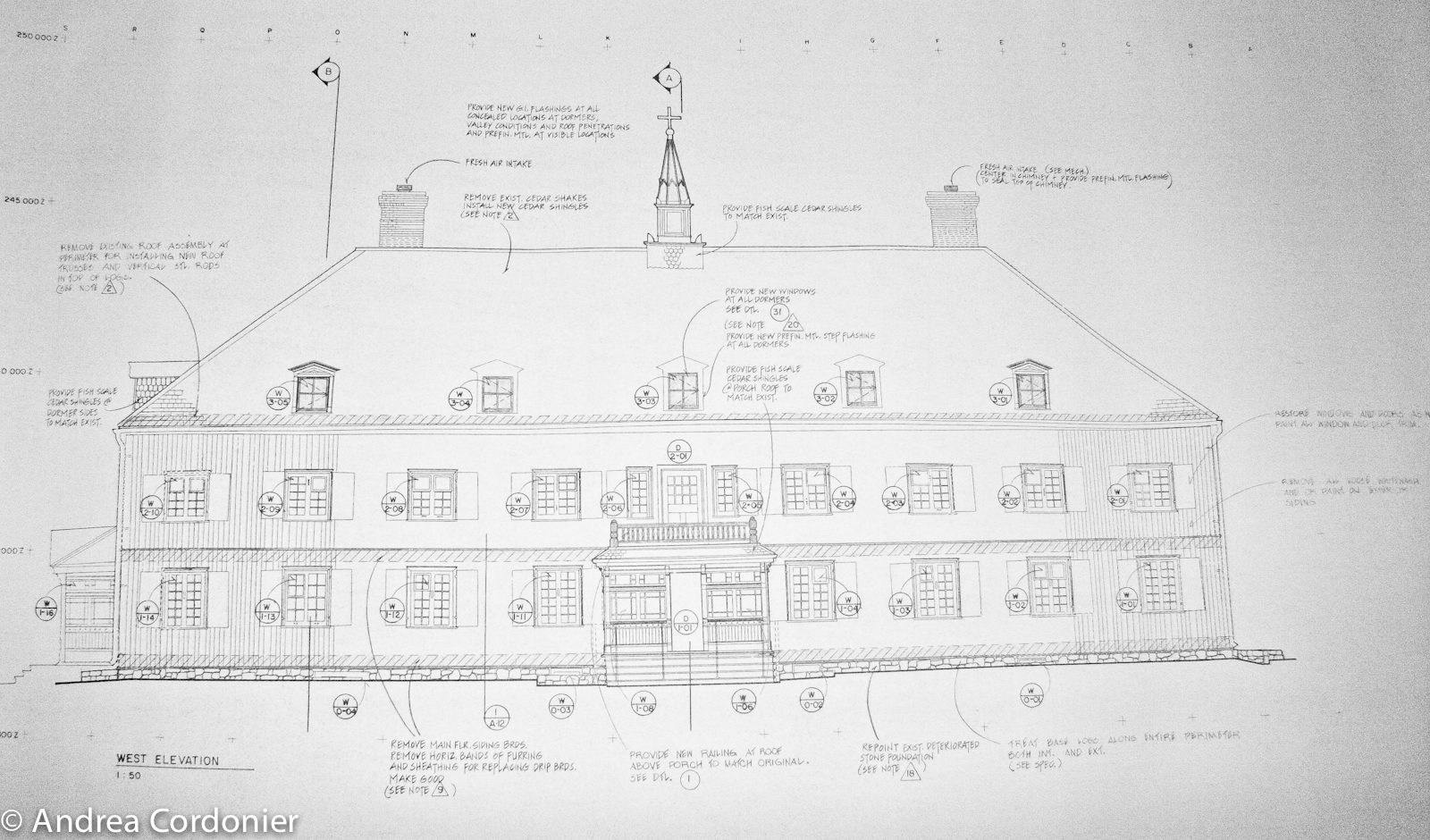

I brazenly roped Phil into giving me a tour of the ‘off limits’ third floor. Walking onto the third floor was like entering a much larger version of my own attic. We talked construction, funding, history, building science, and about the challenges of maintaining old buildings. He disappeared for a few moments and returned with a hefty roll of the museum’s architectural drawings. To my amazement, he presented it to me.

Blueprints are at once treasure troves of knowledge and pieces of art when they are hand-drawn, as these are. I was both surprised and honoured at such a gift.

The moment I set foot out of the museum it began to rain. I pulled off my fleece and slipped the roll into the arm hole, bundling the rest of the jacket around it for safekeeping. By the time I reached the hotel I was soaked but the drawings remained dry.

So glad I skipped the nap.

One response to “Adaptive Reuse (and Reuse and Reuse) at the Grey Nuns’ Convent”

Great article on one of our treasured attractions and historical sites. Thank you for visiting and writing about this special gem. And yes, Phil is one of our best ambassadors in the Saint-Boniface region.