So there I was watching Arrested Development reruns when the Bluth family model home flashed up on screen. It’s the running gag where the turreted McMansion sits alone in desert-like surroundings, where the family lives amongst the staged bowls of plastic fruit waiting for prospective buyers who never come.

And I laugh, of course, because it’s cringeworthy that anyone would build – not to mention live – in a house in the middle of nowhere, a folly of stranded infrastructure. Then I realize I’ve recently seen this very thing, and reality is much less funny than its fictional counterpart.

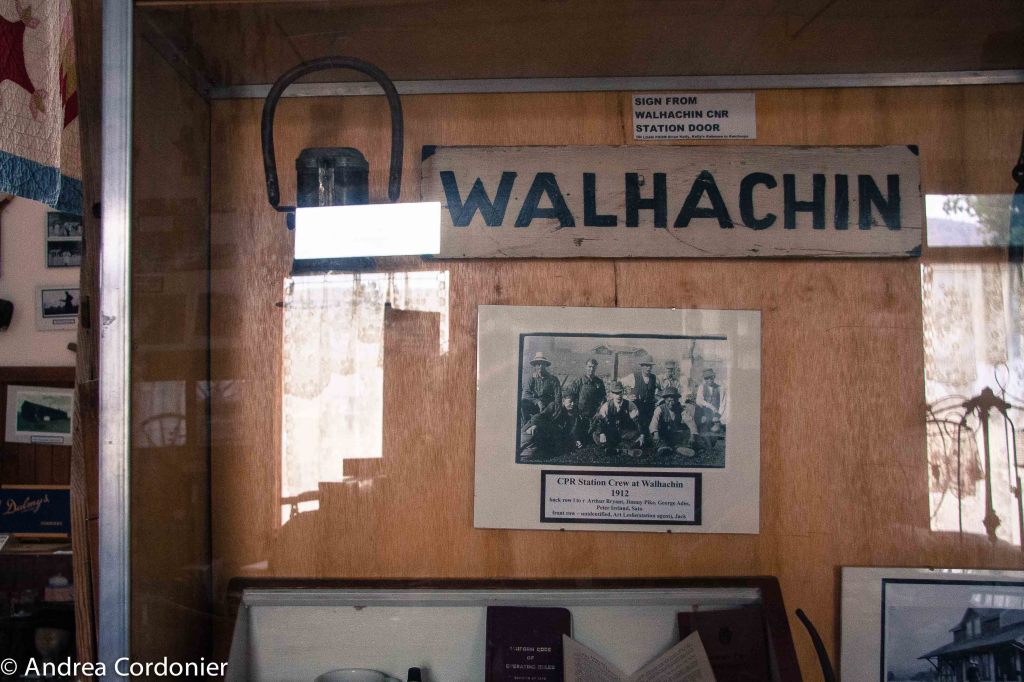

Flashback to our summer of 2014 cross-Canada family vacation and we’re driving one of my favourite scenic stretches of Highway 1. I have travelled this route since I was a kid, so I know this planned subdivision lies not far from the ghost town of Walhachin, originally conceived as a community for titled Englishmen in 1909.

Despite the fact that Walhachin lies in the center of British Columbia’s dry belt, replete with sagebrush and rattlesnakes, American entrepreneur Charles E. Barnes envisioned thousands of acres of lush orchards and a luxury community of gentlemen farmers with fine accommodations, a Chinese laundry, servants, polo grounds, a skating rink, a swimming pool and tennis courts. It would become a cultural haven in the midst of the Canadian wilderness, closed to outsiders who didn’t meet social expectations.

![Photo taken 1910 Photographer: Unknown Source #D-03169 [1] Category:British Columbia public domain photographs](https://habicurious.com/wp-content/uploads/Screen-Shot-2014-11-27-at-8.57.15-PM.png)

![Photo taken 1910 Photographer: Unknown Source #D-03171 [1] Category:British Columbia public domain photographs](https://habicurious.com/wp-content/uploads/Screen-Shot-2014-11-27-at-9.10.36-PM.png)

But two absolutes would bring about its rapid demise.

Although the Thompson River flowed below, it was neither technologically nor economically feasible to pump water uphill. So residents built 12 miles of flumes to pipe water from Snohoosh Lake in the north downhill to the townsite. It was meant to be a temporary measure; a permanent solution would be installed when the growing ventures showed a profit. But the hastily-built wooden flumes were not up to the task of providing adequate water flow. Crops grew well enough but not in a high enough volume to show consistent profit. Not everyone’s water needs could be met.

Then Britain’s declaration of war against Germany in 1914 landed the fatal blow. The men headed off to fight for King and county, and many women returned to the comforts of their homeland. By 1922, no Englishmen were left in Walhachin.

Today, there are a few houses, a few fruiting trees, and a few local memory-keepers, but precious else left of the promised land. Are we so stubborn or ignorant that we prefer not to learn from the history that lies before our very eyes?

Further reading:

B.C. Historian/Writer Michael Kluckner

The Short Season of High Society by Graham Chandler, Legion Magazine

Walhachin, Catastrophe or Camelot? by Joan Weir

The Age of Waterlilies by Theresa Kishkan

Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs, University of British Columbia

5 responses to “Arrested Developments”

There’s a wonderful old book, Wild Honey, by Frederick Niven. My dad gave me a copy years ago and its dust jacket is missing and I’ve never been able to decide whether it’s fiction or memoir. The protagonist walks the canyon (and hops on boxcars) and his commentary on that landscape, those people — well, it’s dated but also pungent and compelling.

Years ago, I almost bought a lot on the eastern side of the community simply because there was a remnant of old foundation wall, with big river-stones in the concrete…

I understand that urge. The whole stretch between Savona and Cache Creek is otherworldly to me. In fact, the entire Fraser Canyon route holds a deep attraction to me. But it always seems I’m passing through; I would like to spend a good week doing that stretch, during another time of the year than mid-summer, when I could do more exploring on foot and not feel like I’m bound to go from ‘A’ to ‘B’…. It’s a bit of the land that time forgot. What is it that’s there for me exactly, I wonder?

Oh, I loved reading this, Andrea. Sigh.

Thanks T! I could feel your presence when I walked around town 🙂