EXHIBITION:

Shame & Prejudice: A Story of Resilience by Kent Monkman

06 January – 08 April 2018 @ the Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queens, Kingston, ON

It’s interesting, artist Kent Monkman said.

When he posts a new painting to social media the predictable response is around 500 likes. But this one, he said gesturing to the projection, was different. This time, his accounts blew up to the tune of half a million hits.

The Scream, it appears, was da bomb. And I am not surprised.

For tonight’s crowd, Monkman is a rock star preaching to the converted. He introduces his current show Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience and leads the audience at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queens through the evolution of his work, from abstract symbolism to – literally – inserting himself into the historic picture via his gender-bending, sequin-wearing, two-spirit alter ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. Think a seventies Cree Cher with ripped abs and Louboutins.

Monkman’s Miss Chief pictures embrace the language of the pornography of violence to take a powerful swipe at Canada’s ruinous colonialism; some of these works are – arguably – obscene, indecent, crude, lewd, dirty, vulgar, erotic, titillating, suggestive, sexy and risqué. They’re also laugh-out-loud funny because they flip the usual narrative and power structure on its head. This is Canadian history laid bare.

The Miss Chiefs are accomplished, audacious, clever, button-pushing and absurd, and the explosive size of the paintings guarantee no point shall be missed (though you’ll want to move closer to catch all the cleverness).

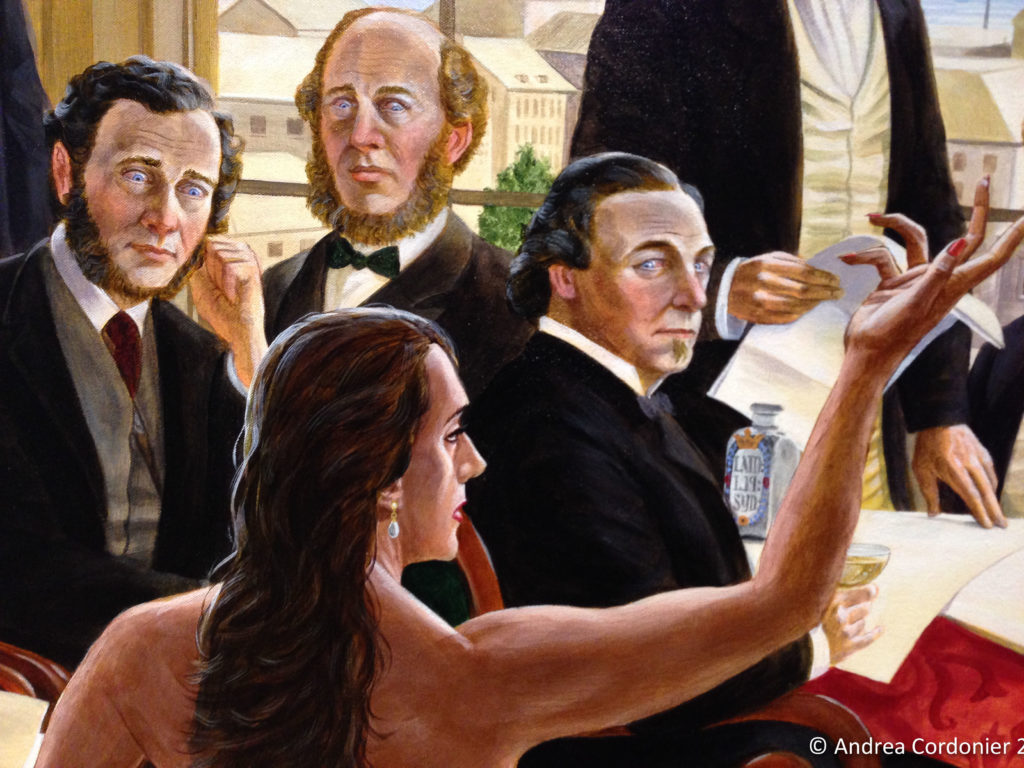

Monkman paints in a virtuoso realistic style from the light-filled pastoral landscapes of eighteenth and nineteenth century European and North American Romanticism with a healthy overlay of BDSM. It’s a flashy bodice-ripper style of the indigenous alt-history sort, a choice bit of allegory well done. It is satisfying to watch the Fathers of Confederation taking one (or 10) for the team for a change. There is allegorical payback here, if not justice exactly.

But The Scream is an entirely different act.

What Monkman accomplishes with the libidinous in the Miss Chief pictures, he accomplishes here through the abject parental horror of the unthinkable question: What would you do if your children (and their children, and their children) were stolen? What would be left for you? How could you ever get past that?

The Scream is not a “What if?” scenario; it is an amalgam of the defining moment of Canada’s very real history of the theft and forcible confinement of indigenous children to church-administered and state-funded residential schools.

This was a homegrown act of war, an enactment of the final solution to the Indian Problem, cultural genocide as it was finally named at the Truth & Reconciliation Commission of Canada in 2015. It would be the gift that would keep on giving, seven generations on.

I’m not surprised that The Scream got 500,000 likes because this universal image is deeply relatable, because its success pivots on empathy. A viewer can put themselves in the picture, understand the pain of the enormous loss, and feel disgust at its devastating legacy. In marketing parlance this means the message is “sticky,” that it has an enduring ability to rise above the tidal wave of information and messaging and stay with the viewer over the longterm, perhaps even prompting them to action.

This stickiness of The Scream could become a foundational starting point to a broader public knowledge acquisition and transfer around the history of residential schools in Canada. We may now have a greater percentage of media stories about indigenous people and increased quote/unquote awareness, but I think we are failing at articulating and transferring the basics:

- Why should the general population care about what happened to indigenous peoples?

- How can the general population begin to understand the systemic problems arising from the residential schools and their ongoing impacts on Canadian life?

- What might simple talking points look like that would provide the language for rudimentary (factual) discussions about the issues?

I think the massive feedback for The Scream indicates that Monkman has inadvertently created a missing link in that education process. It makes sense to move his painting out of the art galleries and into schools, community centers, city halls and other common and accessible public spaces, hanging it right up there next to the Queen. We aren’t in need of a volume of messages, but we are in desperate need of direct, relatable and transferable ones.