[pullquote]I am awake, but ’tis not time to rise, neither have I slept enough…I am awake, yet not in paine, anguish or feare, as thousands are. ~ 17th Century religious meditation for the dead of night[/pullquote]

With winter darkness falling at 5:00pm, I’m lucky to remain vertically upright until nine. After a hard day’s labour, a hot bath and two fingers of wine, I struggle to make it to eight.

I don’t mind the pseudo-narcolepsy as much as the psychological loss I feel for the interrupted sleep that follows. Two a.m. is my new six, and I lie awake for a couple of anxious hours. I try to remain still so as not to disturb Husband. But at some point I muddle in the pile of clothes on the floor, trolling the gloom for familiar textures – fleece, flannel, wool – then laptop, charging cord, and slippers. I squeak my way downstairs to the couch, fighting the anxiety of unintentional wakefulness. Some reading, some writing, some panic and, at some point, I doze off for a couple of more hours. I’ve coined it my Two Sleeps and feel a modicum of gratitude that the cat has ceased trampling my head for the trifecta.

Eight hours of restful sleep, we are repeatedly told, is optimal for health and performance. But the sleep pattern that is so new – and startling – to me is hardly new to human history. E. Roger Ekirch argues in his book At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past, that segmented, or bifurcated, sleep was the norm for pre-industrialized society, “that awakening naturally was routine, not the consequence of disturbed or fitful slumber.”

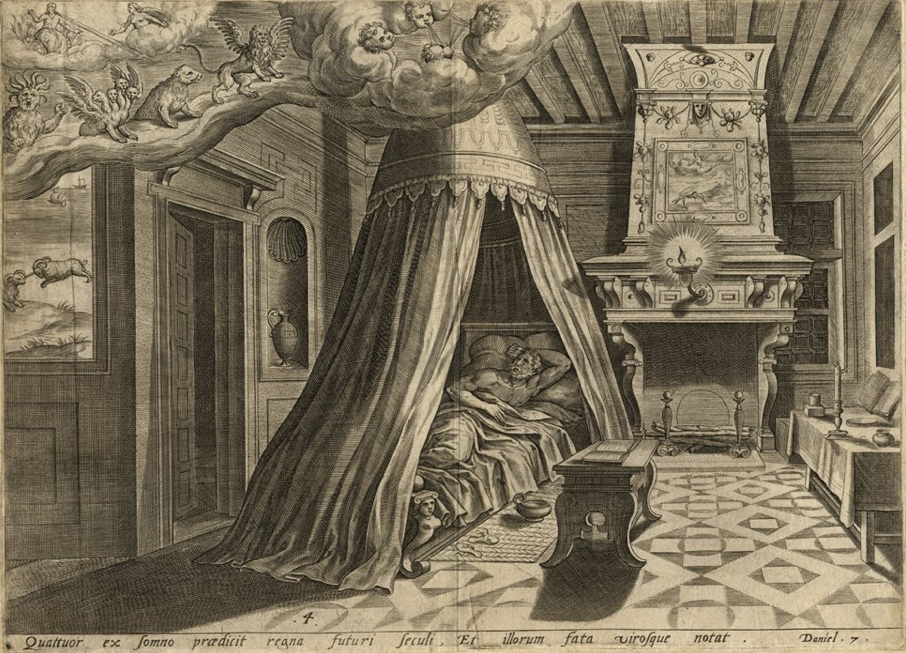

Segmented sleep is described as two major intervals of sleep, of similar duration, bridged by a prolonged period of quiet wakefulness. Historically, the First Sleep generally ended around midnight and was considered the superior sleep cycle, one’s “beauty rest.” Second Sleep followed the prolonged period of “watch,” ending with morning light. Ekirch discovered more than 700 references to First and Second Sleep in literature and oral history, extending back to Plutarch, Virgil and Homer, through St. Benedict and John Locke, to The Tiv of modern Nigeria.

Western Europeans, and later North American settlers, below the “middling orders” took to their beds soon after nightfall for a variety of reasons: lack of central lighting; to conserve costly fuel and light; concerns for personal safety; winter cold; fatigue from manual labour; illness; and crowded housing conditions with little personal space or furniture. They always had bedmates, sometimes multiples, of family or strangers. The wealthy also shared their beds, but by the late 17th century, artificial lighting and the growth of “nightlife” extended their days into the small hours of the morning, permanently shifting their sleep habits. All of the first world eventually followed suit.

Just after midnight, the common people awoke to urinate, begin domestic duties, meditate, interpret dreams, converse with their bedmates and make love. Falling into bed exhausted, couples would wake after first sleep refreshed, “when they have more enjoyment” and “do it better.” 16th Century physician Laurent Joubert advised those wishing to conceive to “get back to sleep again if possible. If not, at least to remain in bed and relax while talking together joyfully.” Students studied, poets wrote, thieves committed petty crimes, monks prayed, witches practiced magic and tribal members communed with one another. Mid-night wakefulness offered a surprising variety of rewards, including staving off loneliness and anxiety.

I can think of more than a few seasonal things I’ve always wanted to do in the middle of the night (happily, petty thieving and witchery aren’t amongst them). Swim in the river on a hot summer’s night. Fire up the sauna. Snowshoe under a star-filled sky. Wander the village in pajamas and drink tea on the park benches. Skate on the frozen river by lamplight. Paddle by the light of the moon. I joke with friends about flashing a Bat-Signal in the sky to alert others to my wakefulness, but I know there are simpler – if not as cool – technological solutions to making contact.

So why, I wonder, must this sleep disruption be a solitary, anxious endeavour? Why must it be a curse and not a creative, soulful blessing?

One response to “A Reasonable Expectation of Undisturbed Rest”

My husband recently read about the history of segmented sleep — in Harpers maybe? — and it made sense to me. Like you, I go to bed early, unless there’s a reason not to — dinner party, etc. I read and then sleep. And often find myself awake in the wee hours. I actually like to come downstairs and sit at my desk in the utter quiet, sometimes working on something or as often as not, simply musing. When I was younger and had small children at home, it was troubling to me to wake in the night. I’d count up the hours of sleep I’d had and worry that I wouldn’t be any shape to face the morning. But now it feels like a luxury somehow. And if I’m away from home, in a city, I like to stand by the window and watch whatever it is that happens at night in Paris or Prague. The night seems full of possibilities!